(All photos can be enlarged by clicking on them. A reader has informed me that the photos were throwing the text out of line, with photos sometimes covering part of my text. Very frustrating! So, I've reduced the size of all the photos. Hopefully that will help. Now, they're just too small to really see while reading through, so you may have to click on individual photos & enlarge them that way. Damn blogger!)

When I was a child, a teacher of mine, learning that I aspired to be a doctor, warned me that because I was a girl, I could only hope to become a nurse. Soon after that, I was with several family members at a reception for Democratic party volunteers when my mother, outraged by my teacher's comment, introduced herself to Congresswoman Lindy Boggs and told her the story. The congresswoman did exactly what my mother hoped she would do - encouraged me to think that girls could aspire to do and be anything. As my mother tells it, "Lindy Boggs, in a navy skirt and navy stockings, knelt down, getting white chalky floor dust on her stockings. She took your little face in her hands and told you that she was a girl AND a member of Congress and that YOU could be anything too - not just a nurse, but even a doctor." And so, over the years, I have paid attention to the Boggs family, including the life and work of Lindy's daughter, Cokie Roberts.

Unfortunately, Roberts seems to become more of a flake every year. Check out this latest. Roberts, asked about Obama vacationing in Hawaii, says that although she understands Obama went to high school there and has a grandmother there, it still is an "odd" choice for his vacation because it will make him seen too "exotic" to voters.

And she had said this twice in the last two days. Does she not know Hawaii is just part of the United States?

Hey, Cokie, why are you spouting Republican talking points about Obama being "exotic" (which is code for "black")? Are you yet another fair-skinned daughter of the old South (and it's not just fair-skinned daughters of the South, actually) who just can not, will not vote for a black man? I know maman was born at Brunswick Plantation in Pointe Coupee and that papa, Congressman Hale Boggs, was a signer of the Southern Manifesto (which, in response to Brown v Board of Education, condemned desegregation), opposed the 1964 Voting Rights Act, and that decades before that, he had led the movement to break the power of populist Huey Long and Long's political machine. Is it still that kind of thing, Cokie?

I come from slaveholding people too, Cokie. And for several months now, I've been thinking of posting my photos of the old plantation on my blog, and I'm not exactly sure why. I just know I am furious about the racism I am still hearing from Democratic members of my own family who just will not vote for Obama. Maybe I want to hold a mirror up here - to ask those of us who descend from slaveholding people to really think about race and oppression, to demand that we be honest and look fearlessly and relentlessly at what dwells deep in our hearts, to challenge us to join the fucking twenty first century here. Are we going to do it? Are lifelong Democrats going to actually vote for McCain now? Mother? Little sister? How 'bout you, Cokie? "Exotic" indeed, Madam Roberts. Our people have been on the wrong side of history, the wrong side of humanity for far too long.

the plantation (with my daughter on the porch)

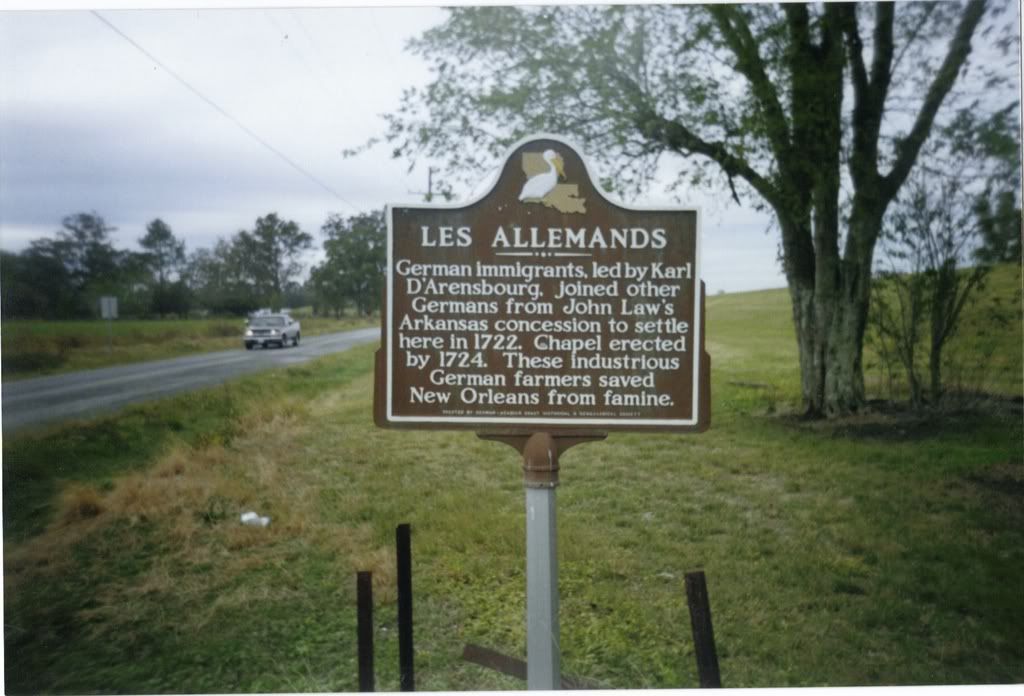

It's called St. Amelie. It's on the River Road, on the east bank of St. James Parish. It was a middle class sugar plantation back in the day. It was one of several such homes in the area that my family, German and Acadian settlers of the German Acadian Coast, owned from the time the Germans settled as indentured servants in 1724 through when the Acadians settled as refugees from French Nova Scotia in the 1760s to the time of the Hymelia Crevasse of 1903 (Hymel - pronounced "E-mel" - was the family name. Hymelia was one of the plantations they owned. A crevasse is a levee breach and resulting flood. The Hymelia Crevasse of 1903 was a levee breach that sent floodwaters from my family's riverfront property across hundreds of miles. For many old time planter families who had struggled to keep planting profitable post-slavery, including mine, this loss of crops, land, possessions, and farming implements was what finally pushed them out of the farming business forever.).

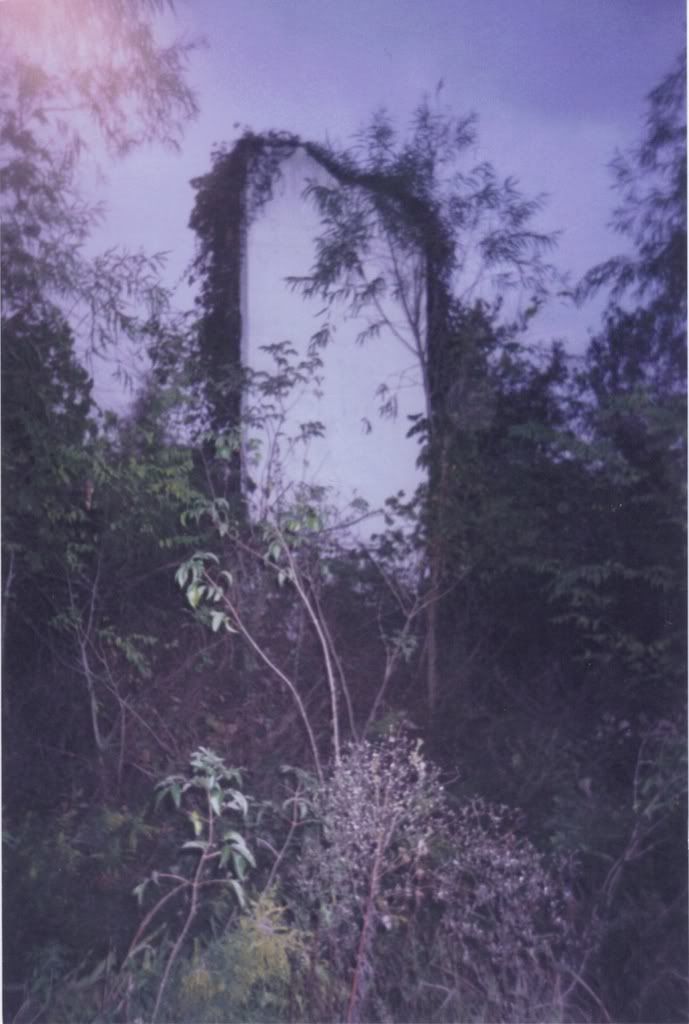

St. Amelie is the only house my family owned that is still standing. The rest of the houses ended up in the Mississippi River as the river changed course over the centuries or ended up just crumbling over time, abandoned or unprofitable after the Civil War. One, Minnie Plantation (thus named by Clairville Himel because Minnie was the nickname of his bride, Lavonia), is now just a chimney in the middle of a muddy cane field (thank you to my husband for tromping through the mud to get this photo for me, and for thinking to bring me back a single brick):

what's left of Minnie Plantation:

Minnie Plantation's chimney from a distance:

The following reports regarding slaves involve Drausin and Clairville Himel (uncles to Mary Himel Blanchard, see below)

Assumption Parish, 1852: Virginie, a nineteen-year-old woman of color, seeks to recover freedom for herself and her five-month-old daughter named Philomène. Virginie represents that she, her mother, and her two sisters were formerly the property of the late Joseph Bernard. During his lifetime, Bernard took the three women to Cincinnati, Ohio, where in 1835 he legally emancipated them. Bernard and the three women then went to St. Louis, where in 1836 Bernard took steps to ensure the validity of the deed of emancipation. Virginie contends that she and her family lived free “publicly and openly” from 1835 until 1847, with the knowledge of Bernard’s heirs. In 1847, however, she was sold back into slavery by one Théodule Mollère at the instance of Bernard’s heirs. She is now in the possession of Drausin Himel. Virginie seeks an order declaring her and her daughter, born since her emancipation, free and commanding Drausin Himel to pay compensation for her services at the rate of $180 per year until she is restored to liberty. She seeks the appointment of a “curator ad hoc” to represent her daughter.

Assumption Parish, 1852: Celesie, a twenty-three-year-old woman of color, seeks to recover freedom for herself and her two mulatto children, Victorine and Gustave. Celesie asserts that she, her mother, and her two sisters were formerly the property of the late Joseph Bernard. In his lifetime, Bernard took the women to Cincinnati, where in 1835 he legally emancipated them. Bernard and the women then went to St. Louis, where he took steps to ensure the validity of the deed of emancipation. Celesie contends that her family lived free "publicly and openly" from 1835 until 1847, with the knowledge of Bernard’s heirs. In 1847, however, she was sold back into slavery by Théodule Mollère at the instance of Bernard’s heirs. She is now in the possession of Clairville Himel. Celesie seeks an order declaring her and her two children, born since her emancipation, free and commanding Himel to pay compensation for her services at the rate of $180 per year. She seeks the appointment of a "curator ad hoc" for her children. A related petition describes Celesie, her mother, and her sisters as "mulatto" women.

St. James Parish, 1849-1850: Clairville Hymel represents that Henri Baudet falsely and maliciously accused him, in an affidavit before a justice of the peace, of having incited a slave named Valery to run away, and of concealing and stealing him. Hymel further claims that he was “publickly arrested” as a result of the charge and arraigned before a grand jury, although later released. Hymel contends that Valery is not Baudet’s slave but his and, inasmuch as the accusation was “without reasonable or probable cause,” he has suffered damages. He prays the court to condemn Baudet to pay the damages plus costs of suit.

Drausin's grave in Labadieville cemetery

An oak tree stands where a plantation called Welcome belonging to my family used to be. Whenever you find an oak tree in the middle of nothing on the River Road, a plantation once stood there.

St. Amelie is not particularly impressive by modern housing standards. It's much smaller than most modern homes, with just two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and a dining room (no grand rooms like Tara in "Gone With the Wind" or anything). And it's probably much less impressive than Brunswick where Lindy Boggs was born, but even so, it's still nicer than what poor whites had in centuries past and far nicer than what slaves had.

slave quarters in St. James Parish

St. Amelie from the side:

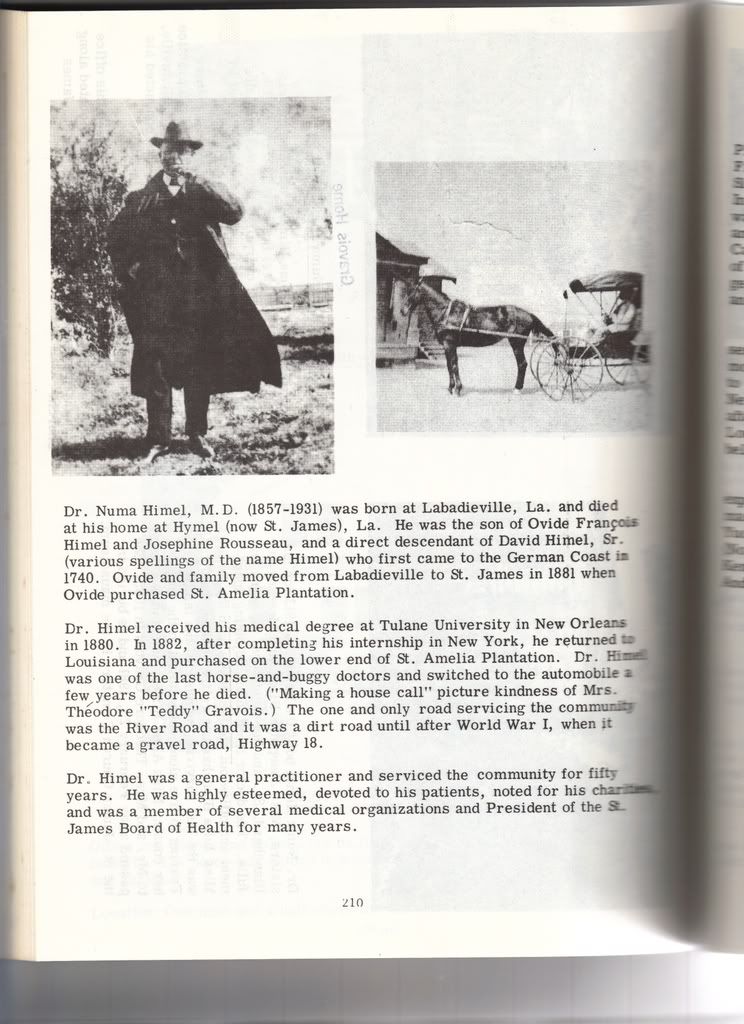

The other side view. My great-grandfather's uncle, Dr. Numa Himel (all lived at St. Amelie together), visited patients by horse and buggy until well into the twentieth century.

River Road residents who needed a doctor would hang a white flag outside, and the doctor would know to stop. Most families had no cash and the doctor often got paid with chickens or eggs. As Dr. Himel aged, he wanted a partner to join him in providing medical care in the area, but it was difficult to entice another doctor to come work in the country for mere chickens and eggs, so he offered a young doctor from New Orleans a free spot on his land on which to build a home if the doctor would relocate to St. James. Here you can see the newer brick home, built by the younger doctor, Dr. Campbell. Notice the wire between the two houses - this ran between the two doctors' offices and was, in the days before telephones, how the doctors summoned one another.

This is the front porch, which my mother remembers being washed with ice water daily by maids so that it stayed really shiny. My part of the family was not generally welcomed at the old Creole plantation because we were, scandalously enough, Irish half-breeds, but my mother was once sent here for the summer as punishment because she had failed her Catholic school French class. As a result, she had to spend three months out in the country, bored to death, with two old maid great aunts who only spoke French to her (although they were bilingual schoolteachers - talk about learning a language by the immersion method!). The aunts found it shocking that their brother's own grandchild had actually failed French and took that fact to be further proof of the folly of his having married a lowly Irish woman. Said they of their sister-in-law, "She can scrub her floors and wash her clothes as much as she wants, but she will always have the taint and smell of the Irish."

My Irish great grandmother, Catherine Caroline Mullen Blanchard (1897-1977; seated, right)

This is an old sugar kettle that is now being used as a planter behind St. Amelie. In the old days, slaves cooked down the cane over intense heat through a series of kettles until only granulated sugar remained. Because Louisiana has only a semi-tropical climate and does sometimes get freezing temperatures in winter (while sugar is usually a cash crop only in frostless tropical climates because the crop takes many months to mature and can not survive a freeze), the cane crops here had to be feverishly harvested round the clock as soon as they matured, lest the stalks be turned to mush by a single overnight freeze. And so during the harvest season slaves on Louisiana sugar plantations worked in exceptionally brutal conditions. Seven days a week, they worked at least two eight hour shifts a day and sometimes twenty hours a day (the Code Noir required that slaves be given Sundays off, but that law was routinely ignored on sugar plantations during harvest season). As a result, slaves on south Louisiana sugar plantations had fewer live births, suffered more illness, experienced more fatigue-induced accidents, and faced much shorter life expectancy than did other slaves of the era.

In one of the two bedrooms, my great grandfather's crib, already an antique when he slept in it, can still be seen (bottom of the photo). Another family now owns the home and lives in it. Luckily, they have kept EVERYTHING original except for, they say, hanging their clothes in the closet. They did have a kitchen added on to the actual house; in the old days, kitchens were always separate buildings because of the risk of fire. In their old age, the aunts sold this place to proper French strangers because they found that preferable to having Irish halfbreeds inherit it.

I should mention that all photos of the interior of the home were taken when I just knocked on the door and introduced myself one day. Mr. and Mrs. (very French surname) understood right away who I was and how I was related to the previous owners, but even so, their graciousness in allowing a stranger to walk through and photograph every inch of their home was extraordinary.

my great-grandfather, Arthur Eli Blanchard II, as a baby (1891-1971)

wash basin

These days, few families farm in this area, although agribusiness does still grow some sugar cane here. Large blocks of land - former plantations - were sold decades ago to petro-chemical companies like Exxon, Shell, breast implant and Agent Orange specialist Dow Chemical, Union Carbide (responsible for a 1984 chemical release in India that it admits killed 3,000 people and Green Peace claims ultimately killed 20,000), and Monsanto (if you don't already hate and fear the evil Monsanto, click on the links to find out more about their genetically modified food, their terminator seeds, the recombinant bovine growth hormone in your dairy products and how they've sued farmers advertising rBGH-free products, their efforts to get patents on the breeding and herding of pigs, their responsibility for 56 environmental superfund sites in the U.S., and how they sued a 70 year old Canadian farmer for "seed stealing" because their genetically modified seed was carried by the wind onto his land - after years of their assurances that genetically modified seeds knew how to stay in their own designated spaces and would never contaminate naturally occurring species). The companies purchasing the land have sometimes destroyed grand homes of great historical significance, but in a few cases of relatively responsible corporate citizenship, companies have paid restoration costs, and old large plantation homes on the grounds of sprawling petro-chemical processing plants now serve as on-site meeting rooms.

The families who remain here - mostly the descendents of slaves - face extremely elevated risks of miscarriages, birth defects, cancer, and other ailments due to water, air, and soil contamination from the chemical plants (as The Who might say, meet the new boss, same as the old boss). Near St. Amelie is a large plantation open to tourists that is called Oak Alley. Here in Louisiana, however, this entire region is now known to us as Cancer Alley.

the entrance to the Monsanto plant (notice the row of oak trees, indicating that this was once the entryway to a plantation):

chemical plants have been built around the old cemetery...:

...down the street from St. Amelie and tourist mecca Oak Alley (below):

the aunts' gravesite in St. James cemetery (Himel and Blanchard):

the dining room fireplace with original tools, clock, and mantel knick-knacks:

another fireplace, still more Victorian basins (there were some in each room):

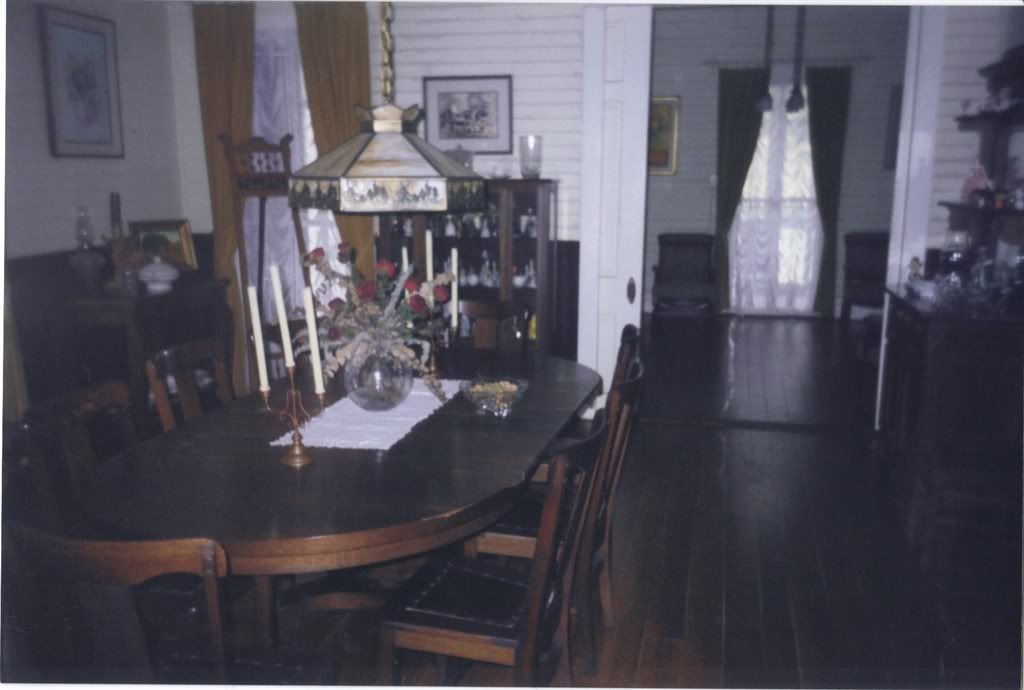

This is the dining room. To the left is a sideboard that was used as an ice cart. My grandmother vividly remembers from her visits that during meals, a maid would take each diner's drink and keep it on ice in the cart, then hand the drink over each time the diner wanted a sip.

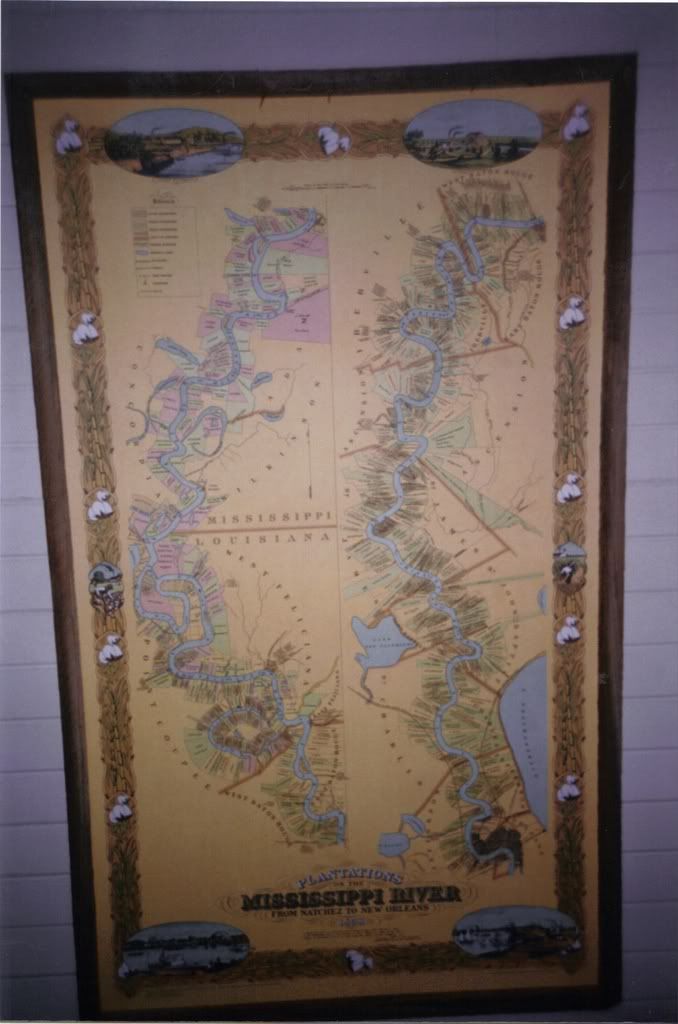

This is the Persac map in the dining room. Most plantations on the River Road had a copy of this map. Persac had surveyed the area, and the map showed every plantation along the river and named the owner of each. The names are difficult to read because the river turns so many times and because land grants were, in the French custom, long and narrow so that each plantation had access to the river, where goods were shipped and people could travel by boat (the long, narrow strips make reading the owners' names very difficult).

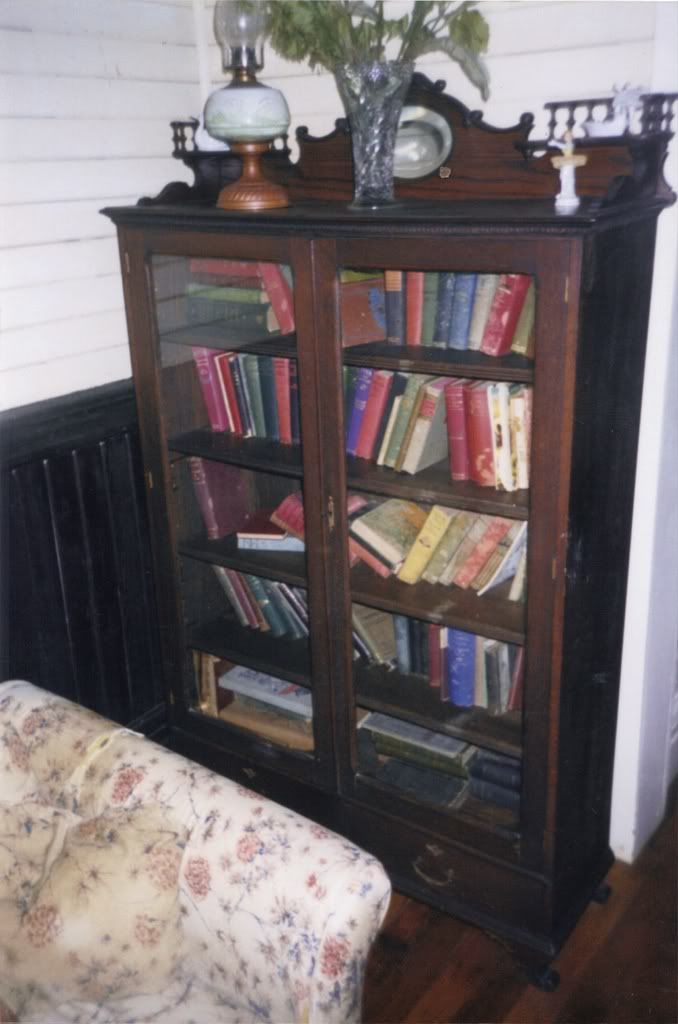

A hallway bookcase with the original books belonging to my great grandfather's uncle, Dr. Numa Himel. My great grandfather and his two sisters returned from New Orleans to this house, the childhood home of their mother, Mary Himel Blanchard, when they were small children after their father, Acadian riverboat pilot Captain Arthur Blanchard, died suddenly in his thirties. When her elderly great aunts sold this place, my mother was permitted to choose one thing from the home for herself (the custom was that when a plantation was sold, the furnishings went with the house). My mother chose a set of books - the complete works of Sir Walter Scott. The books were originally given to my great-great grandmother, Mary Himel Blanchard, by her brother, Dr. Numa Himel, one or two each Christmas, over about a twenty year period in the second half of the nineteenth century. Inside each book is an inscription with the siblings' names, "Merry Christmas," the date (December 24 or 25 and the year), and sometimes a brief note. These books were the bestsellers of that period and greatly influenced the worldview of white antebellum southerners. The books, such as "Rob Roy," presented themes like honor, chivalry, and gender in ways that epitomized the values of white southerners - particularly the planter classes - on the eve of the Civil War. My mother still has them, although some sustained a little water damage during the famous "May third" flood of 1978. When my mother fled south Louisiana ahead of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, she packed only necessities. In the final hours before Katrina made landfall, as the winds were already frighteningly intense and the electricitiy had already gone out, my husband drove sixty miles to my English teacher mother's home to rescue her important documents, photographs, an antique set of the complete works of William Shakespeare, and the Sir Walter Scott books from the old plantation.

My great-great grandmother, Mary Himel Blanchard (1865-1945)

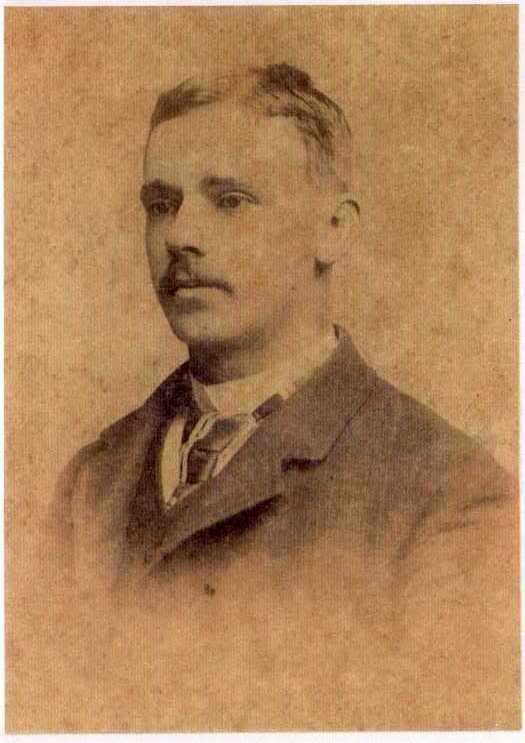

My great-great grandfather, Arthur Eli Blanchard (1858-1895)

Below is the steamship G.W. Sentell (G.W. as in "George Washington"), purchased in July, 1891, as a joint venture of the Blanchard Brothers (one of several steamships owned over the years). It was owned by C.J. Blanchard, the eldest brother, who served as her Master; by Arthur Blanchard (above) who served as Chief Engineer; by Max A. Blanchard (who was considered Max, Jr., although the brothers' father was Maximin Telesphore Blanchard, a son of Acadian refugees from French Nova Scotia); and 2 friends or investors: Frank Dunos & Nicolas Burg. Max, Jr., & Edgar served as pilots. In August of 1892, according to the Daily Picayune, C.J. had a large B mounted between the stacks, which had already been painted a bright red. The Sentell was a sternwheel packet with a wood hull built in Jeffersonville, Indiana. On December 28, 1894, while docked near Hillary St in Carrollton, she burned & sunk. The exact cause of the fire was unknown.

Federal records of shipping-related deaths and accidents show the Blanchard brothers were peculiarly prone to losing black deckhands and screwmen during the night, without witnesses, to fatal accidents or drowning. Granted, the river trade was very dangerous in those days, but the Blanchard brothers seemed to lose black sailors in particular with alarming frequency. Eventually, the respected and well-known C.J. Blanchard would face trial for murder over one such case once his ship had docked in St. Louis, apparently outraging New Orleans newspaper reporters and editorial writers.

Below, another steamboat owned by Max Blanchard, Sr., the E.W. Cole. Max Blanchard purchased this boat in 1886 from Captain Thomas L. Morse. In 1888 (after winning the state lottery) he spent over $8,000 to overhaul her. She then began to ply Bayou Lafourche as a regular packet. The Cole was 201 ft long, 31 ft in the beam with 5.4 ft depth of hold, reportedly the largest boat to regularly steam on the bayou. The Cole was built in 1880 at Jeffersonville, Ill. She was snagged and sunk on January 1, 1891. At the time of the sinking, Max Blanchard was master; O. Blanchard and Frank Hymel were mates; Max Blanchard, Jr., and Camil Jacobs were pilots; A.E. Blanchard and Charles Gillham were engineers; Amede Blanchard was carpenter. As with the Sentell above, a large "B" can be seen between the smokestacks.

hallway at St. Amelie - wash basin

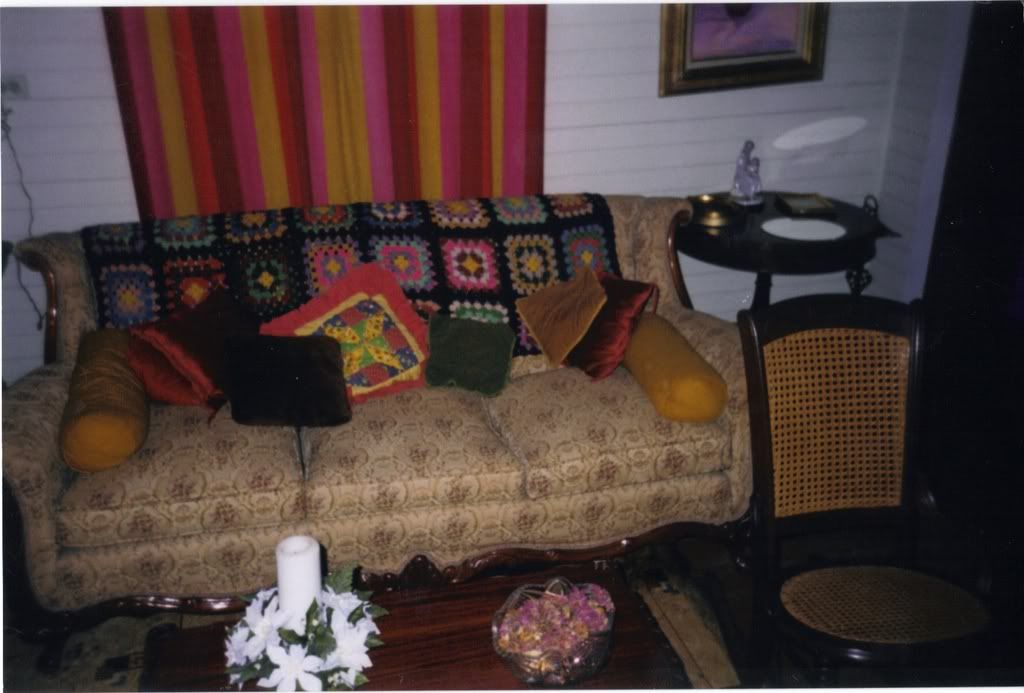

The camel hide sofas in the living room. My mother remembers that children were not allowed to play in this room or sit on this furniture (which was fine with her since apparently camel hide is really scratchy). I can't imagine any other space inside where kids could have played; I guess they just stayed outside most of the time. My grandmother relates that when her father was disciplined as a boy, his mother would dress him as a girl and force him to stand on the levee for all passersby to see. In his teens, my great-grandfather's idea of fun was to line up "pickaninnies" and see how many he could jump his horse over. God. Maybe "American Idol" is not such hideous entertainment after all.

The hallway, facing the front door and porch. The piece of furniture on the right was for holding hats and coats, obviously, but my mother remembers that the drawer in the bottom was the only place in the house where the aunts kept anything fun for children. On rainy days they would open it, and inside were hundreds of scrolls the aunts had made from newspaper comics. Each one had two sticks, and my mother would hold the sticks to unroll the scrolls and enjoy reading the comics inside (hey, the aunts didn't have television).

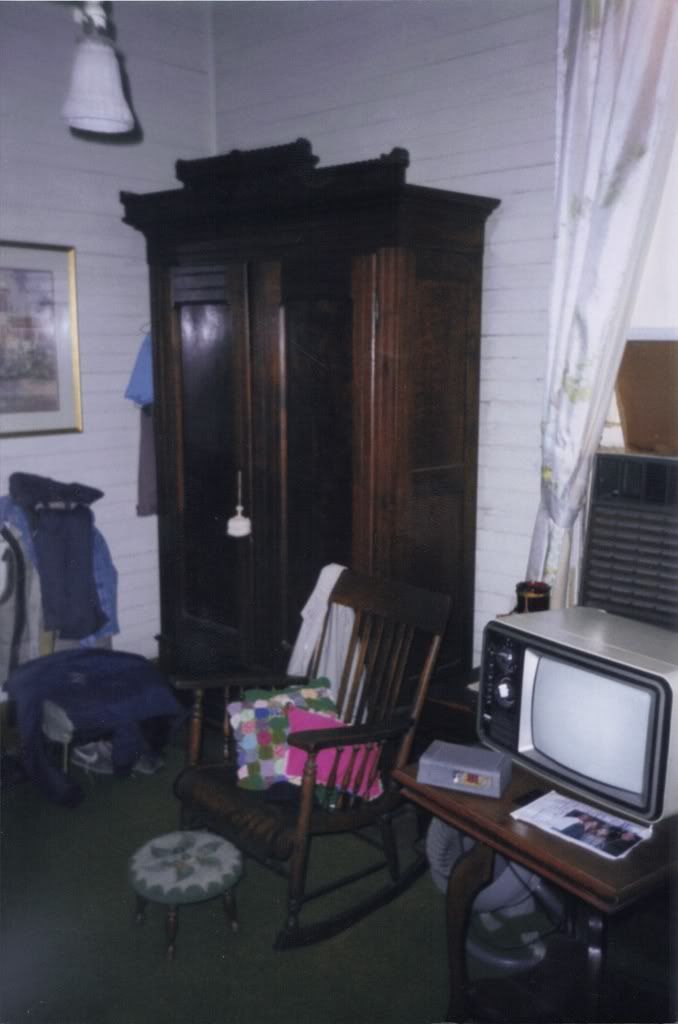

bedroom 2 - wardrobe

bedroom 2 - dresser

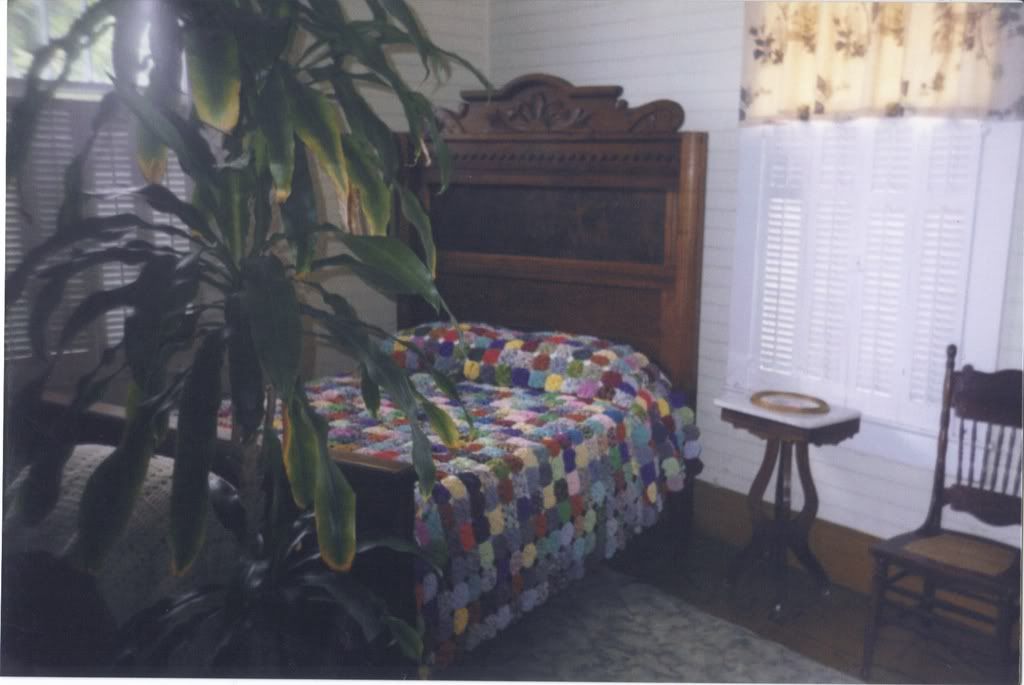

In bedroom two, a tester bed (pronounced "tee-ster"), which was basically a canopy bed and had mosquito netting draped over the whole thing, although someone has in recent years chopped off the four corner poles.

So, there it is - Cokie, Mother, little sister - our past, as a people. Take a good look - at the shiny porch floor and the ice cart maintained by maids; at the slave quarters; at the cane fields; at the old sugar kettle that meant backbreaking, round the clock labor and early death to so many human beings; at Mark Twain's beloved glamorous Mississippi River steamboats on which black sailors who displeased could simply disappear.

When will we finally move beyond who we as a people, as a region, have been?

Why are lifelong Democrats I love doing what you're doing? Cokie says Obama is "exotic." My mother says he "can't be trusted." My former Carter delegate aunt is horrified by the prospect of his being the nominee.

He's not supposed to get to live in the white house, right? I mean, not St. Amelie on River Road, not Brunswick in Pointe Coupee, and not the other white house at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue either, yes?

10 comments:

Outstanding post. I'm going to link to it tomorrow.

Mark Twain detested Walter Scott and the false nobility he inspired among southern slave holders. I forget the exact reference, but he mocks Scott at some point during Huckleberry Finn.

Thanks! I worked my butt off linking the photos. Sometimes blogspot has a mind of its own. It goes back and changes what I've already done.

Yes, I don't imagine that Twain would have thought much of the Scott outlook among southerners! I'll have to try to find the quote. Now I'm curious.

It's nice to have books that have been in the family for almost 140 years, inscribed and everything. My mother has promised that they will eventually be mine. I've been coveting them since I was about 12 years old.

Here via K.

I have the Twain quotes. There's more than one.

I can send them if you like.

Love, C.

Here are Twain's most pertinent comments about Scott and the South (BTW, I still love Scott's works, and will read one of his books at least once a year).

You find his first remarks about Scott, his work and the South in his memoir of his youthful experience on the Mississippi steamboats, Life on the Mississippi, concerning Mardi Gras (though he isn't entirely correct with all his facts about Mardi Gra; for instance the first Mardi Gras parades were in Mobile).

"Mardi-Gras is of course a relic of the French and Spanish occupation; but I judge that the religious feature has been pretty well knocked out of it now. Sir Walter has got the advantage of the gentlemen of the cowl and rosary, and he will stay. His medieval business, supplemented by the monsters and the oddities, and the pleasant creatures from fairy-land, is finer to look at than the poor fantastic inventions and performances of the reveling rabble of the priest's day, and serves quite as well, perhaps, to emphasize the day and admonish men that the grace-line between the worldly season and the holy one is reached.

This Mardi-Gras pageant was the exclusive possession of New Orleans until recently. But now it has spread to Memphis and St. Louis and Baltimore. It has probably reached its limit. It is a thing which could hardly exist in the practical North; would certainly last but a very brief time; as brief a time as it would last in London. For the soul of it is the romantic, not the funny and the grotesque. Take away the romantic mysteries, the kings and knights and big-sounding titles, and Mardi-Gras would die, down there in the South. The very feature that keeps it alive in the South--girly-girly romance--would kill it in the North or in London. Puck and Punch, and the press universal, would fall upon it and make merciless fun of it, and its first exhibition would be also its last."

Then, from a letter to his married sister, Pamela Moffett (March, 1859), "It has been said that a Scotchman has not seen the world until he has seen Edinburgh; and I think that I may say that an American has not seen the United States until he as seen Mardi-Gras in New Orleans."

To add to understanding how Twain reached his position, I have noticed in my readings in the last 2 - 3 years of Scotland's splendid detective and police fiction, how much the fantasy romantization of the Old South and the American Western play in the cultural life. It's referred to in the background and in the music playing, and even the decor of clubs and homes, and sometimes even the plots. The audience is probably not much surprised to see this in Rankin's Rebus series,for instance. It's even more obvious in the television series made based on these books. But this audience was surprised to find how much C&W music is in even the television series, Monarch of the Glen.

Twain, like many reasonable people, objected to history and romance brought together, and you have to think, particularly with the creation of the KKK, he had more than one solid point on his side. However, yhe shelves of West Point's library was packed with historical romance novels.

General Grant, who won the Civil War for President Lincoln, read Scott and Cooper both with greater pleasure than he pursued his studies while he was at West Point. (p. 12, Perry, in Grant and Twain, from Grant a Biography)

Love, C.

Hi, Foxessa. Thank you for the information about Twain, New Orleans, and Scott.

One question - you wrote that Grant won the war for Lincoln. I had always thought that Sherman did, what with that march to the sea and burning everything in his path (lol). I thought that was what finally did it.

Hi!

I saw a link to you through What Tami Said.

Great post!

I have seen lots of scholarly materials on cases involving liberating slaves, similar to what you have described. If you go to ssrn.com, you can find some stuff written by someone named Jones. Last name begins with a B, I believe.

Thanks, PioneerValleyWoman.

I will check that site out!

I want to take ALL of the slave-related materials I have and put them online. I've read that this is the most helpful thing descedants of slaveholders can do to help trace the families of slaves - take anything you have and put it online as soon as possible (per Ball, author of "Slaves in the Family," and others). Some of it seems to have ended up in storage (my husband's black hole) when we moved, but I am about to go back to the library, start making copies, and post it all somewhere. It haunts me to think that right NOW, this information could be the link someone is looking for.

You're welcome. More stuff: The Petitions Project might be a good example of a website/searchable database...Petitions submitted to state legislatures regarding slavery. Have you gone to the state archives to find the materials on the cases? I bet the cases were reported in LexisNexis, a database for court decisions.

I got some of the steamboat material (like the federal accident reports) at the state archives. I haven't tried Lexis-Nexis. I am out of law school at the moment (and personal subscriptions to Lexis-Nexus are quite expensive), but when I am once again in law school, I will try that route. That's an interesting idea!

What an interesting post.

It sees we are third cousins. That is if my consanguinity table reading is correct. My great-great grandfather Hector Adam Himel was your great-great grandmother's brother. I would love to talk with you sometime.

Have you finished law school?

Post a Comment